A Harvard MBA Versus One Bitcoin

Jesse Myers | Chief Operating Officer

Jul 5, 2023

In 2012, Harvard’s illustrious MBA program did something unusual.

For the 25th reunion of the Class of 1986, they sent out a survey that asked intimate questions about these Harvard Business School grads’ lives and careers, and then they published the results. As far as I can tell, they never published anything like this again.

The median annual earnings for these high-power executives was $350k. More revealing, however, was what the survey indicated about the net worths of these ~50-year-old Harvard grads. In 2011, the median net worth for the HBS Class of 1986 was $6m.

Of course, adjusted for asset price inflation, that would mean something like $10m today. (It also is worth underlining that this would have been the midpoint in the set of reported net worths, and presumably the average would have been much higher as a result of some very high earners at the top end of the distribution.)

When I first came across this number, it shocked me. It frankly feels low. This is Harvard Business School we’re talking about.

And this is the cohort of HBS grads who went out into the world at the tail end of the 80s, in the heyday of opportunity for corporate executives to deliver value through cost-cutting, offshoring, M&A, and financial engineering. They would have been perfectly positioned to take leadership positions in new-fangled internet companies in the 90s, and would have been active participants in the 2000s housing boom.

Our culture glorifies the Harvard MBA today because of the massive success of this era of Reagan Republicans who were trained in the latest techniques of cutting-edge managerial science and whipped into the zealous religion of “shareholder profits above all else” before being unleashed upon the world. These grads are why Harvard Business School is known as “the West Point of capitalism.”

It probably goes without saying, but these opportunities are no longer open to recent HBS grads.

The low-hanging fruit of driving shareholder value through the classic mechanisms of managerial science listed above have all been plucked. You weren’t an MBA in the 80s – too bad, you missed it.

Every generation has its big opportunity

You may have missed the low-hanging fruit of the 80s, but there’s always some new wave of opportunity. The challenge is to spot it before everyone else. What could it be for this generation?

If you’re a millennial (born 1981-96) or zoomer (born 1997-2012), you’ve probably thought about how impossible retirement sounds.

It was different for the boomers (born 1946-64).

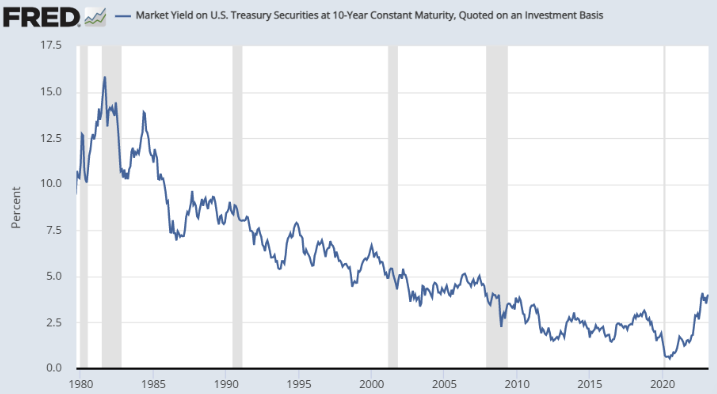

Interest rates were driven down from 15% in 1981 to ~0% over 40 years, causing equities markets and home prices to soar. If you got in on the ground floor – like the boomers who entered the workforce in the 70s, bought houses in the 80s, and maxed out their 401k contributions for decades along the way – you did great.

But there’s no more runway to drive down interest rates. Home prices simply cannot soar like they did over the last 40 years, when adjusted for real terms.

In the early 1980s, the median home price was 2x the median income. Mortgage rates were 15%.

Today, the median home price is 10x the median income. Mortgage rates are 7%.

Those numbers net out to make home ownership ~2.5x more expensive today than in the early 80s.

If you’re a young person looking for a winning strategy to build wealth, it’s all terribly disheartening. We’ve been told to put faith in the tried-and-true wisdom of responsibly growing personal wealth: pay down your mortgage, invest in stocks, trust that asset valuations will go up.

That may have worked over the last 40 years of low inflation and declining interest rates (which is why it became the accepted wisdom)… but millennials and zoomers will not benefit from the same conditions going forward.

Those tailwinds are over – in fact, they’ve now reversed.

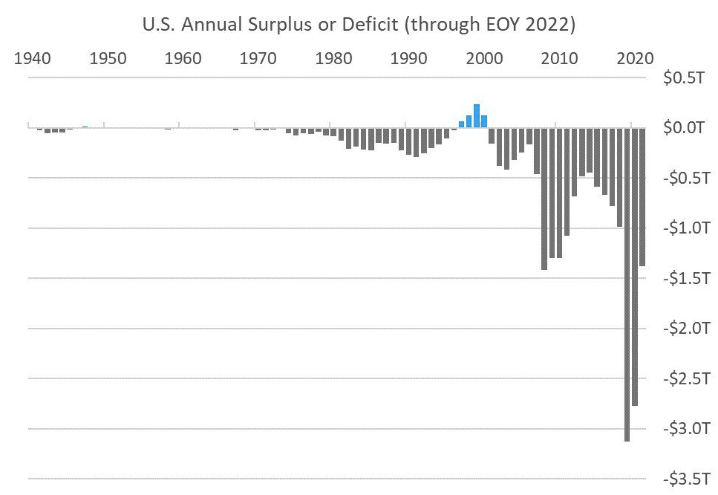

The US now has $31T in national debt (~130% debt/GDP). We’ve been running ~$1T budget deficits for a decade, and now that interest rates are rising, the interest expense on the national debt is rising with it. If interest rates get to 10%, the US will have $3T in annual interest expense just to service its national debt. All in all, we’re heading towards $4T in annual budget deficit. The only solution is to print that money, which is done by issuing even more debt, making the whole problem that much worse.

This is called a debt spiral, and there’s no way out – it’s just math.

Having painted that gloomy picture of why the next 40 years structurally cannot be like the last 40 years, we can look ahead to ask where the big opportunity may lie for this generation.

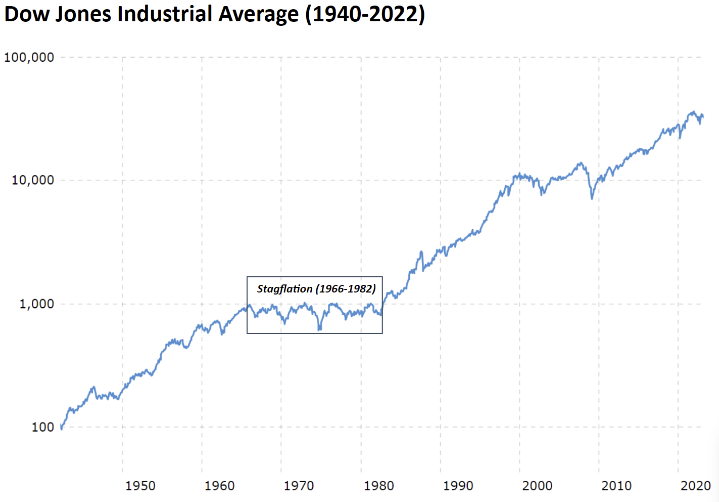

Since real estate and equities outperformed with monetary policy tailwinds, it stands to reason that they will underperform with monetary policy headwinds, as they did during 1970s stagflation.

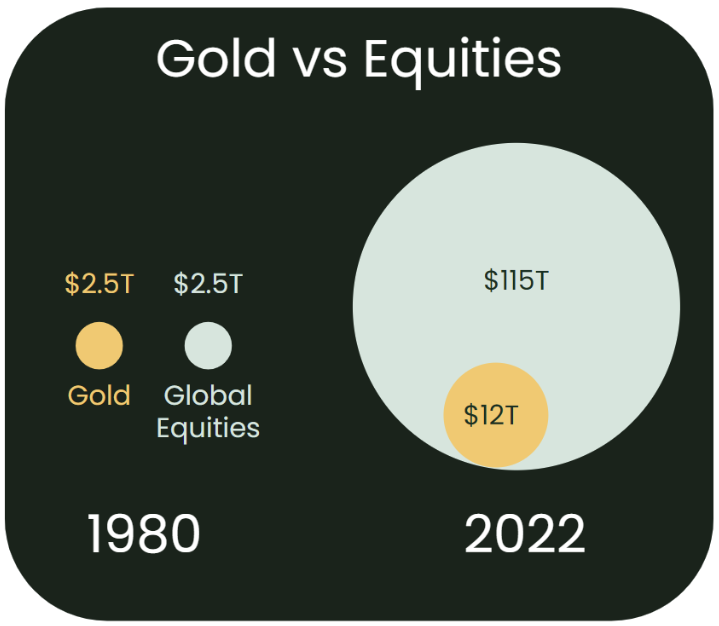

Conversely, the assets that performed poorly over the last 40 years are now poised to perform well under the opposite conditions, as they did during 1970s stagflation. The best performing asset of the 70s was gold; since then, it has underperformed.

The trade of a generation

It would be easy to conclude that gold is poised to have a great decade and leave it at that, but if we zoom out a bit, there’s an even bigger opportunity at hand.

The reason gold did well in the 70s is because it is “hard money.” In simple terms, it’s hard to make more of. You can’t easily print it, you have to mine it.

This makes hard money desirable to hold when governments are printing a lot of money and inflation is running hot – exactly what the US did in the 1970s, in order to soft-default on its debts in the wake of Vietnam.

So, hard money did well in the stagflation of the 1970s. And because of the math of our present debt spiral, we’re entering an era of inevitable money printing and high inflation. Gold will probably do very well in the decades ahead, but let’s not forget that we are also living through the Digital Revolution.

What if there was something else that was poised to perform even better than gold… a new, still tiny, digitally-native hard money on the global asset scene…

Something whose properties set it on a deterministic path to become gold for the Internet age. And once it becomes gold 2.0, it doesn’t stop on its pre-programmed path to get more scarce and more valuable, such that it starts to rival and even surpass the previously unmatched capabilities of real estate as a scarce store-of-value. And along this whole journey, it enables the disruption and disintermediation of entire industries involved in the traditional functions of value storage (banking), transmission (payments), and associated services (financial services).

Why, such a wide-sweeping overhaul of the world of value would be tantamount to a second Internet Revolution – an Internet of Value to complement the existing Internet of Information.

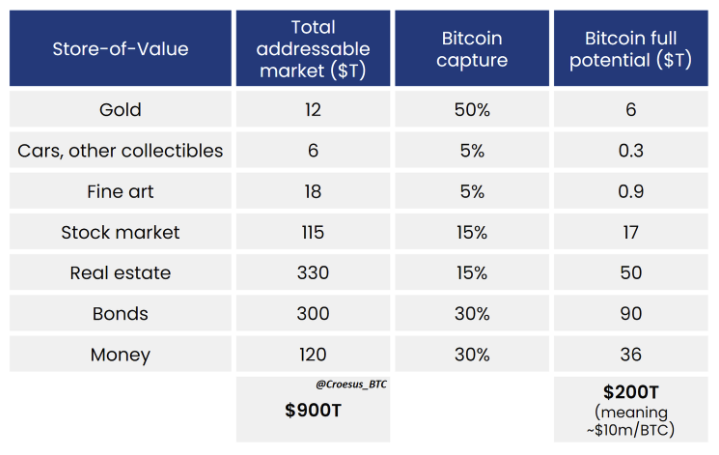

If there was such an asset, it could very feasibly eat ~$200T of the world’s ~$900T in assets.

I may be wrong, but Bitcoin seems to be exactly this asset, in the early stages of exactly this journey. That’s a bold claim, and will likely sound preposterous on the surface to many readers, but that’s my conclusion after thousands of hours of trying to disprove the mechanics underway.

As far as I can tell, all that has to happen for this to play out is for Bitcoin to keep doubling in scarcity, which is programmed into the protocol to happen every 210,000 blocks – meaning, every 4 years.

Which is to say, all that separates Bitcoin from becoming the most important asset of the 21st century is the passage of time. Since that is a given, Bitcoin’s rise appears inevitable – pre-programmed and deterministic.

Tying it all together

While I am tempted to launch further into all that, it’s time to bring our focus back to the HBS Class of 1986 who have been waiting in the wings patiently for the author to get to the point.

If Bitcoin becomes a ~$200T asset, each of the 21M Bitcoin that will ever exist will grow to be worth $10M apiece. The same value as the median net worth of a Harvard MBA from the Class of ‘86.

For millennials and zoomers, the path to achieving financial success on the scale of the legendary Harvard MBA’s of our parents’ generation may be as simple as accumulating one whole Bitcoin.

The best of the boomers achieved $10M in wealth through leveraging an unprecedented era of equities and real estate price appreciation; the best of the millennials and zoomers may achieve the same wealth simply by plucking the low-hanging fruit of accumulating Bitcoin before the rest of the world has caught on.

(And the cleverest of the boomers will realize they can ride this wave too.)